PEOPLE DIE ON THE STREET TO THE PEPPER GARDEN

100 Stories from 100 No Longer Published Newspapers, 100 Years Ago, in NFT

By Denny JA

The pandemic in the era of 100 years ago was completely different. It is narrated: “People died on the road to the pepper fields. They were panic. But the elders in the community, responded to the pandemic, by inviting residents to pray together and ask for rain to fall.”

This is one of the stories from thousands of stories in various parts of Indonesia. All stories happened about a hundred years ago. The story was recorded by 100 editions of newspapers, in that era. Now the newspaper has been out of print for a long time. Not all of us remember the names of these 9 newspapers. All in ancient language. That was Indonesian 100 years ago. Or Dutch 100 years ago. I can't read from the newspaper directly. The paper is very fragile. But a photographer had already taken pictures of the old newspaper collection. I only read stories from enlarged newspaper shots.

The names of the 9 newspapers were: Bintang Timor, 1866 edition. Sinar Terang, 1888 edition, to De Preanger Bode, 1899 edition. Now 100 editions of 9 newspapers that are 100 years old have been in NFT (Non-Fungible Token). A total of 100 newspaper editions became a 100 NFT series. This is a fusion of the old story, 100 years ago, with the latest technology (blockchain technology) to become NFT.

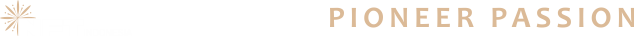

Monday, November 12, 1888.

The Sinar Terang Newspaper, about 133 years ago, wrote:

"It has been a month since the bustling trading area on the coast of Teluk Betung City has been hit by a severe smallpox outbreak."

“People died on the streets to the pepper fields. The plague did subside and disappeared."

"However, cholera instead spread rapidly to villages."

“In 15 days, 98 people contracted cholera and 43 people died from it."

“People prayed to God for safety and it rained because it had not rained for a long time."

"After receiving a report of the situation from a controleur, the local government distributed medicine to the community, while urging them to clean and protect their environment."

Of the 98 people who contracted cholera, about 50 percent (43 people) died. What a high percentage of deaths. Of the 98 people who contracted cholera, about 50 percent (43 people) died. What can the government do? At that time there was no vaccine. Not yet known Working From Home. Don't know about social distancing. The government only asked them to clean the environment and distribute medicine. While the people just pray, and ask for rain. Such was the recording of the atmosphere in Indonesia, in Teluk Betung City, Bandar Lampung, 133 years ago.

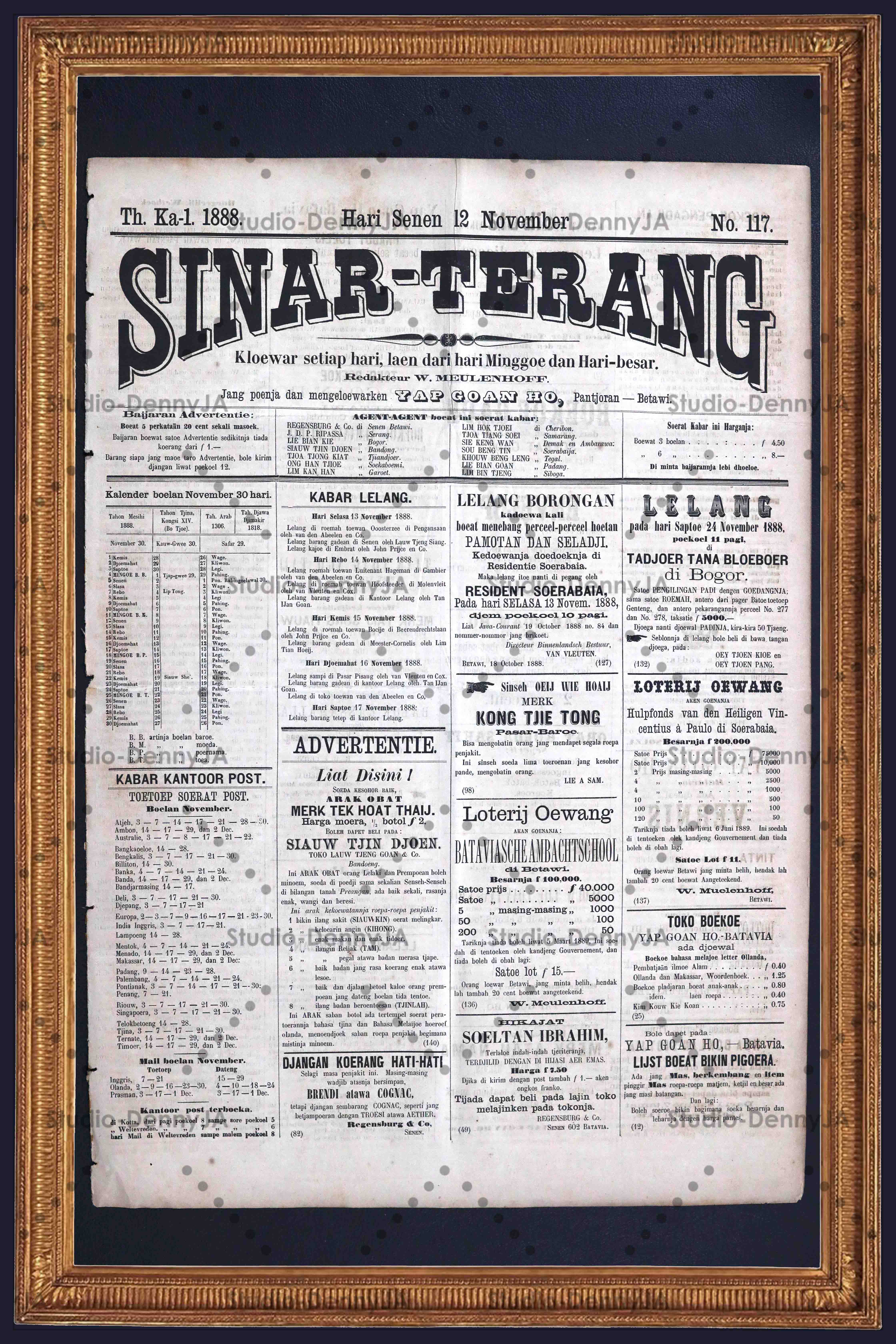

Tuesday, March 1, 1904.

The Betawi Star Newspaper, which was published 117 years ago, reported:

“Governor General Rooseboom and Head of the Ministry of Education, Religion and Crafts Mr. Abendanon acts."

"He ordered all the Regents in Java and Madura to build schools for the children of the country (Indigenous), Indonesia, in their respective areas of authority."

"Even so, the number of students who are allowed to study in each school, outside of the aristocratic and aristocratic circles is still limited."

This is the year 1904, 41 years before Indonesia's independence. And 24 years before 1928, the year the national consciousness of “One Indonesia” emerged. The colonizers, the Dutch, actually started education for the natives. The priority is only the elite family. Outside of the elite exit, the number of students was limited. This is the beginning of the educational tradition that began in colonial areas. The people are not prioritized. Widespread education for the masses finally only expanded when Indonesia became independent.

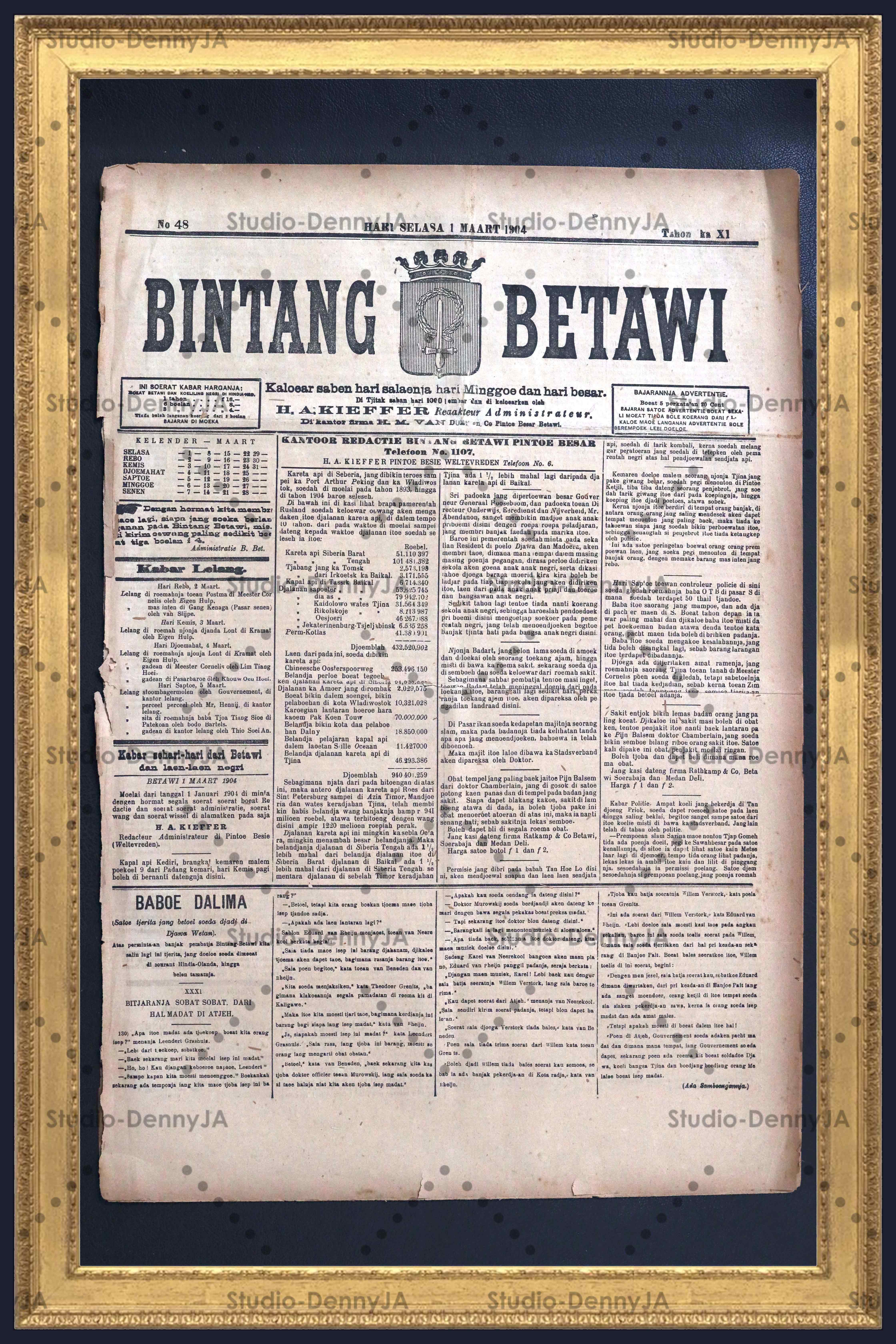

November 20, 1921.

Tjaja Soematra Newspaper reported 100 years ago:

"All the Boemiputera Unions in Tapanuli and West Sumatra held large meetings/deliberations in Sibolga."

"The substance of the meeting was to strengthen the spirit of unity in Sumatra to break away as a 'conquered or colonized nation'.

"Then together we rise to become an independent nation and human being."

This happened in 1921, 24 years before Indonesia's independence. This happened 4 years before 1928, the year of the rise of One Indonesia. Even the awareness to rise up against the invaders, for an independent Indonesia, the roots of nationalism have grown far in remote areas, outside the city of Jakarta, which will later become the center of the capital city.

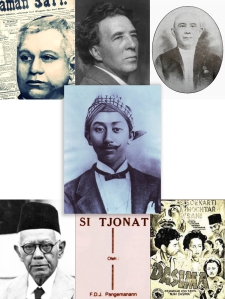

This is an example of news from three newspapers: Sinar Terang, Bintang Betawi, and Tjaja Soematra. These three newspapers have not been published for a long time. I now have 100 editions of similar newspapers, original copies, from 9 newspaper companies. A historian, JJ Rizal, helped trace the origin of the 9 newspapers. When did each newspaper first appear? Who is the publisher? When did the newspaper close and why. hat important events happened about each newspaper. From the historical tracing of JJ Rizal, and the study of the author by Irsyad Mohammad, it is known that many great Indonesian and Dutch writers became writers or editors in one of these newspapers.

There was Tirto Adhi Soerjo (1880-1918). He is now known as the father of Indonesian journalism. He writes in Pembrita Betawi and Bintang Betawi Newspapers.

There is also Abdul Muis (1886-1959). He was a journalist, writer, and also an Indonesian politician during the movement. He is the core administrator of the Syarikat Islam. Now Abdul Muis is a National Hero. He wrote extensively in the newspaper De Preanger Bode.

Ever heard of G.P.W. Francis? He was the author of Njai Dasima (1896). This is the famous story of a beautiful native girl who became the mistress of a Dutch official who was close to Governor General Raffles. Francis writes and heads the Bintang Betawi Newspaper.

Jan Fabricius (1871-1964) is also noted. He wrote many theatrical screenplays. His screenplays are often performed in prominent theaters in Rotterdam. He wrote in the newspaper De Preanger Bode. Now the newspaper office has become the office of Pikiran Rakyat Newspaper.

Ever heard of Lie Kim Hok (1853-1912) He is considered the main founder of Malay literature with Chinese nuances. He often writes in Pembrita Betawi newspaper.

The names of the 9 newspapers include:

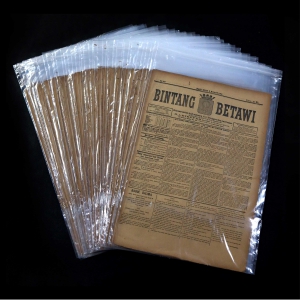

1. Bintang Betawi, 32 Edition, published between March 1, 1904 - June 1, 1904. Old Indonesian. Last published in 1909.

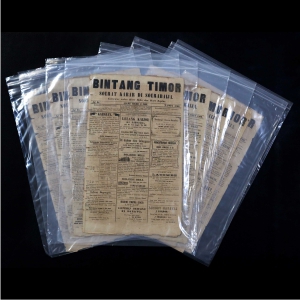

2. Bintang Timor, 10 editions, published between March 1, 1866 - May 5, 1866. Old Indonesian. Last published in 1887.

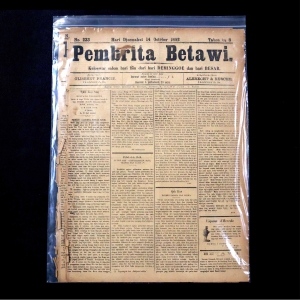

3. Pembrita Betawi, 4 editions, published between October 13, 1892 - October 15, 1892. Old Indonesian. Last published in 1916.

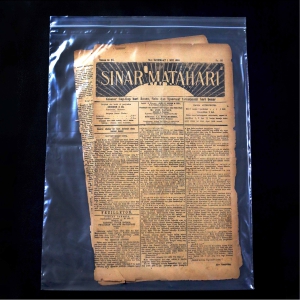

4. Sinar Matahari, 1 edition, published on May 1, 1914. Old Indonesian. Last published in 1919.

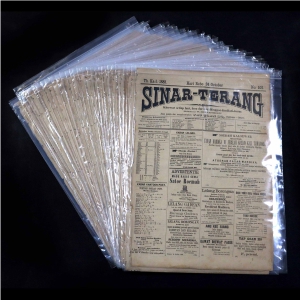

5. Sinar Terang, 34 editions, published between 18 October 1888 and 27 November 1888. Old Indonesian. Last published in 1898.

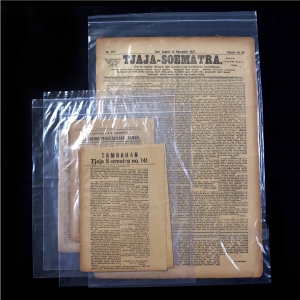

6. Tjaja Soematra, 7 editions, published between 3 November 1921 - 15 December 1921. Old Indonesian language. Last published in 1933.

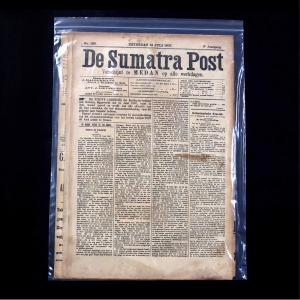

7. De Sumatra Post, 1 edition, published July 13, 1907. Old Dutch. Last published in 1950.

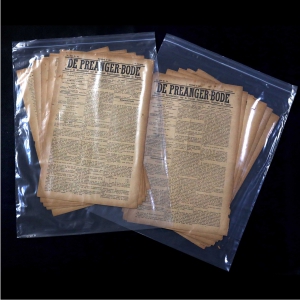

8. De Preanger Bode, 4th edition, published between 12 July 1899 - 21 July 1899. Old Dutch. Last published in 1957.

9. Mataram, 7 editions, published between 21 March 1892 - 26 January 1893. Last published in 1942.

A total of 100 newspaper editions. I keep the print edition. Very carefully I touched this newspaper collection. The paper is very fragile.

A total of 100 editions of the above newspapers, stories in Indonesia and the world about 100 years ago, newspapers that have stopped publishing for a long time, are now made into a 100 NFT series. What is NFT? NFT stands for Non-Fungible Token. It is the latest technology that uses blockchain technology. The same technology succeeded in creating the crypto money that would revolutionize the world of finance. Through NFT, all digital works can be protected. Crypto technology is capable of making digital works individually owned. Therefore, digital works can now be commercialized, traded.

The world of NFT will revolutionize the fine arts. In the digital age, NFT gives new energy to the creation of works of art. These 100 ancient newspapers, from 100 years ago, were also turned into the work of the NFT. Each NFT consists of 1 edition of the newspaper, and historical or unique news summaries have been selected in that edition. The news summary is written in two languages: Indonesian and English.

Three strengths from the series collection of 100 NFT newspaper editions and 100 original copies of this newspaper edition.

First: It is a combination of the NFT series and a 100 year old copy of the original newspaper. It's not only in the form of NFT which is a trend nowadays. It is also in the form of an original copy of the newspaper, the paper is already brittle.

NFT form and original newspaper are in one package.

Second: in the NFT each edition of the newspaper has selected a historical or unique story. There are summaries of 100 stories about society 100 years ago, straight from the newspapers that were published at that time. It is also a historical document of high value. It is especially valuable for those who like Indonesian studies, or colonialism studies, and old cultural events.

Third: this newspaper series is in NFT format and the original copies are the first in the world. Now the NFT series and the original newspaper are owned by NFT Studio Denny JA.

The work of NFT Studio Denny JA has also pioneered the commercial value of NFT in Indonesia. This studio's NFT painting sold at auction for around one billion rupiah (70,000 USD) in April 2021. Also tweets produced by Studio Denny JA, sold for 100 million rupiah (7000 USD) in the same month: April 2021. The product from Studio Denny JA was sold at the Opensea digital auction, for paintings. And sold at a special twitter auction for NFT tweets. The newspaper edition of the NFT 100 series became the third NFT work of the Denny JA Study. The 100 NFT series + original 100 copies of his newspaper are intended at Christie's auction house.

Victor Hugo stated: “Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

The idea of NFT with blockchain technology has indeed come.*

September 2021

Nine Legendary Old Newspapers Denny JA Collection

By JJ Rizal

1. Bintang Betawi - Batavia (Jakarta)

Bintang Betawi first published in 1893. The publisher was J. Kieffer H.M. van Dorp & Co in Batavia and published every day. Kieffer is the leader of the weekly Bintang Barat newspaper and is renowned as the only non-parochial newspaper in Batavia for readers of all races and religions. He was an Indo (mix European descent) born in 1835. Prior to publishing and being the editor of Bintang Betawi until his death in 1904, he was an editor in the Dutch East Indies, in addition to being the founder and publisher of Pemberita Betawi in 1884 and the editor of Bintang Barat in 1888.

E.F. Wiggers, a very prolific Indonesian writer and seasoned journalist, joined Bintang Betawi, on 1893, after leaving Bintang Barat. Apart from Wigers, at Bintang Betawi, other prominent writers also have careers as editors, namely G.P.W. Francis who is famous for his story The Story of Nyai Dasima (1896). Prior to joining Bintang Betawi, Francis was editor of the weekly Court in Bandung. There is one more important figure in Bintang Betawi, namely F.D.J. Pangemanann, a Minahasa (at ethnic that predominantly live in northern part of Sulawesi Island) person who together with Tirto Adhi Soerjo can be said to be the first indigenous writer. His career in journalism began when he worked at the Bintang Betawi newspaper. The sequel entitled "Tjerita Rossina" was published in Bintang Betawi, then republished by Pramoedya Ananta Toer in his book Tempo Doeloe (Old Times).

Kieffer resigned from Bintang Betawi (1905) and was replaced by Francis who changed the name Bintang Betawi to Bintang Batavia until the newspaper stopped publishing in 1909. In his book Seabad Pers Kebangsaan (A Century of National Press) (2007: 20-22) Taufik Rahzen et al. called Bintang Betawi as a newspaper which, apart from being a medium for advertising films, often criticized the Dutch social policies in the Dutch East Indies which were considered to be exploiting the wealth of the Indies. Bintang Betawi also highlighted the fate of thousands of indigenous Indonesians who were discriminated against by the Dutch East Indies government. This newspaper also contributed to the pumping of Asian nationalism through reporting on the Japanese attack and victory over Russia, in Russo-Japanese War 1905.

2. Bintang Timor - Surabaya

Bintang Timor, the newspaper led by J.Z. van den Berg, published in Surabaya, is clearly a pioneer newspaper in the Dutch East Indies. This four-page newspaper, published every Wednesday with a circulation of between 400 and 600 copies. It contains news of events in and around the Dutch East Indies and Singapore. This newspaper also published the prices of commodities in the Singapore market, such as gambier, opium, spices, cotton and yarn for the needs of traders. He opened the “News from Mail” section, in the form of foreign news from Europe, China, and other countries. In addition, this newspaper also quoted news extracts from the Dutch-language Javasche Courant, including news from the government and the colonial bureaucracy of the Dutch East Indies.

Initially, the newspaper published by Gimberg Brothers & Co. on May 10, 1862 was named Bintang Timoor with a double "o". Gimberg Brother & Co. was originally a distributor agent for the Slompret Melajoe newspaper, which was published in Semarang in the early 1860s. In the 1860s. Bintang Timoor underwent an orthographic change in their letterhead to Bintang Timor. Bintang Timor's coverage mostly serves East Java business circles. However, its circulation reaches other cities outside East Java, even as far as Sumatra and Makassar.

In 1868, L. Magniez and O. Th. Schutz led Bintang Timor and made major changes, which was more interested in highlighting topics related to small people such as: poverty, the extortion of the underprivileged in the villages by the colonial apparatus, and the soaring price of rice. However, rising printing prices forced Bintang Timor to increase its subscription price The increase in printing prices made Bintang Timor increase the subscription fee from the previous 15 gulden per year in Surabaya and 17 gulden outside Surabaya. Bintang Timor then omitted the one-year subscription package and only half-year subscription packages were available, with the price then being 10 gulden per 6 months in Surabaya and 12 gulden per 6 months outside Surabaya. Of course, this price makes the subscription fee expensive if you want to take one year, because a year means 20 gulden in Surabaya and outside Surabaya to 22 gulden per year.

The economic depression of the 1880s due to the sudden fall in the prices of coffee and sugar, made banks and trading partners threatened with bankruptcy. This caused many newspapers published since 1875 to die. Bintang Timor is one of the survivors. However, the drag of advertising due to the paralysis of the business world, finally forced Gimberg Brother & Co. in 1887 to declare bankruptcy and death. Bintang Timor, who has been active for 24 years, was finally taken over with a price tag of 24,600 gulden by Baba Tjoa Tjoan Lok, a rich Chinese from Surabaya. This event marked the beginning of the Chinese entering the newspaper business in the Dutch East Indies.

3. De Preanger-Bode - Bandung

The full name of this newspaper is Algemeen Indische Dagblad de Preangerbode and it is with this name that it became famous. However, in its first edition this newspaper used the name De Preangerbode: Nieuws- en Advertentieblad voor de Preanger-Regentschappen, alias De Preangerbode: news and advertisement newspaper for the Priangan (West Java).

Announcements for the publication of this newspaper appeared in the newspapers Java-Bode 23 June 1896 and De Locomotief 26 June 1896. On 6 July 1896. The first edition of Preangerbode was published. This local Bandung newspaper, published by JR de Vries & Co in Bandung and printed by HM van Dorp & Co in Batavia, turned out to be circulating throughout the Dutch East Indies.

Preangerbode contains four pages and is published every Monday. The subscription price is 2.50 gulden half a year for the Dutch East Indies and 3 gulden for the Netherlands. JHLE van Meeverden became the newspaper's first editor-in-chief. Meeverden only briefly led this paper. Then, between 1896 and 1902, Jan Fabricius was the leader, a writer, journalist, and well-known actor. When Fabricius had to return to Haarlem, the Netherlands, in 1902, Preangerbode was sold to Kolff & Co. Since then, the editorial leadership was held by G.L. La Bastide until 1906 and was replaced by Th. E. Stufkens until 1921.

It was during the Stufkens era that the attitude of the editors of Preangerbode became clearer, namely as the mouthpiece of the colonial government. The Preangerbode not only routinely reported on the success of the Dutch East Indies government, but also reactively attacked those deemed to be a danger to the government. The case of Abdul Muis is the most obvious example. Abdul Muis was considered dangerous because he was listed as a member of the Indische Partij which was banned by the governor in 1912. He also together with other members of the Indische Partij, Suwardi Suryaningrat and Tjipto Mangunkusumo, founded the Bumiputra Committee. The Bumiputera Committee was thought to be aiming to participate in "celebrating 100 years of Dutch independence from France”, on 27 November to 1 December 1913. However, it turned out to have the opposite aim and instead sued the Dutch East Indies government with his famous writing "als ik een Nederlander was" (If I Was a Dutchman)[1]. This is what then makes Muis as a print-ready reader on Preangerbode must be excluded at all costs. The reason was found, namely by forbidding Muis to go to Jakarta to accompany his wife who was about to go on a pilgrimage. In fact, Muis was eventually arrested by the police along with Wignjadisastra—the editor of the Kaoem Moeda newspaper—for being involved in printing and distributing the pamphlet “als ik een Nederlander was”.[2]

Preangerbode as a red plate newspaper (government stooge) has a long life and has succeeded in becoming a well-established national local newspaper in business, especially after being held by CW Wormser. This strong person in the world of journalism, apart from controlling De Locomotief, also controlled Het Algemeen Handelsblad voor Nederlands Indie and Het Nieuws van den Dag. It was under Wormser that Preangerbode turned from a local newspaper into a national newspaper with international news. The circulation of Preangerbode was even wider and it was listed as the fourth largest newspaper in the Dutch East Indies. Preangerbode is also listed as the only major newspaper published in two editions: the morning edition and the evening edition.

Although it finally ceased to be published in 1957, Preangerbode remains one of those newspapers that is more than half a century old. This newspaper was stopped when the Dutch East Indies was under Japanese militaristic rule between 1942 and 1945, but in 1946 it was published again under the name Algemeen Bandoengsch Dagblad de Courant. JP Verhoek led Preangerbode until this newspaper was not allowed to be published when the policy of nationalization of foreign companies was implemented. The fate that befell Preangerbode also befell Dutch newspapers in other cities, such as De Java-Bode, Het Nieuws van den Dag, De Nieuwsgier (Jakarta); De Locomotief (Semarang), De Vrije Pers and Nieuw Soerabaiasch Handelsblad (Surabaya).

[1] Ahmad Adam in The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesia (1995, p. 280).

[2] There are also those who say that Abdul Muis was treated this way because he often wrote critical articles in De Preangerbode which, if he didn't pass in De Preangerbode, he sent the article to the De Express newspaper, that well known to be very critical to Dutch Colonial Government.

4. De Sumatra Post - Medan

This newspaper was published in 1899 by J. Hallerman. It is published twice a week. J. Hallerman is a printing businessman of German descent who wants to try his luck in Deli, North Sumatra. This newspaper was initially led by the legal scholar J. van den Brand who was later replaced by Karel Wijnbrandt. In 1903, the name A.J.C.M. Tervooren. This newspaper is headed by AJ Livegoed and JH Ruphan is the editor. The newspaper's longest-serving editor-in-chief is Vierhout.

Although De Sumatra Post is published as a daily with 1 pages, this newspaper does not contain much local news. Most of the pages are for news and developments in Europe, such as the Dreyfus case (a controversial case in France, that inspired Theodorl Herzl to initiate Zionist movement). De Sumatra Post is often referred to as the “Europe Post” which was printed in Sumatra. There, sometimes also appears news about America. In short, this newspaper is a white newspaper. Even if there is local news published there, it will be limited to news about Dutch residents. This “white” newspaper took a lot of advertising, almost on par with the older Deli Courant. It can be said that 60-70% of the cost of publishing De Sumatra Post is saved by advertising.

As a "white" newspaper for plantation owners, its editors are no doubt concerned about the development of the indigenous movement, especially the Sarikat Islam (one of the first Indonesian nationalism movement founded by later National Hero, Hajji Omar Said Tjokroaminoto. Sukarno and many others pioneer of Indonesian national movement during Dutch Colonial era was member of Sarikat Islam), which began to enter Deli in 1913. At this point, Sarikat Islam has become the scapegoat for the plantation coolies who like to fight and stir up violence. Solidarity between coolies, as reflected in their news: “De Aanslagen op Assistenten. De Sjarikat Islam" (The Assaults on Assistants. The Sarikat Islam). However, there was also a story in the De Sumatra Post about a driver who hit a Dutch notary to death, but was released because Raad van Justitie (Council of justice) considered him innocent. A picture of law above power and social class. It's a shame it's only that far, while the fate of the contract coolies who are languishing unbelievably doesn't get any news.

De Sumatra Post ceased publication in 1950 like other old Dutch-language newspapers, due to the nationalization policy of foreign companies.

5. Mataram - Djokdjakarta (Yogyakarta)

The Mataram newspaper can be considered as a marker of the arrival of a new era in the city of Yogyakarta, including in journalism. It was the Mataram newspaper that started to introduce Yogyakarta to the outside world, on par with the cities of Batavia, Surabaya, and Semarang. This newspaper was published when rail transportation made the city of Yogyakarta open from its isolation. In the 1870s, for example, the Semarang to Yogyakarta route via Surakarta was operated. The city is becoming more and more filled with government officials, investors, and tourists[1]. The economy of the Mataram region, which is centered in Yogyakarta, is growing.

The Mataram newspaper was published regularly every day since 1903[2] and died in 1942, along with the entry of Japan and the fall of the Netherlands. This newspaper was printed by H. Buning who was also the main character of other early newspapers in Yogyakarta, such as Darmowarsito and Retnodoemilah. The name Mataram refers to the area of its circulation. The publication of Mataram was also related to the increasing number of Europeans in the interior of Vorstenlanden, aka the Surakarta and Yogyakarta areas.

The Mataram newspaper cannot be separated from the name of the prominent journalist Halkema who is the editor-in-chief of the Dutch-speaking Mataram. Actually there is a well-known name Halkema, but in the affairs of the Mataram newspaper, W. Halkema is involved, namely the oldest Halkema. He was born around 1830 or earlier, because by 1850 he was already in charge of a priyayi school in Banyumas. He worked as a resident assistant in Sambas before starting his career as a journalist. In 1879, he became editor of a Javanese language daily, Darmowarsito, in Yogyakarta. In late 1883 to 1885, he joined Bintang Timor as editor. Until the end of his life he continued to fill his time by writing, including for newspapers. W. Halkema is a polyglot, he claims to be able to teach English, French, and German, besides being able to speak Dutch, Malay, and Javanese.

[1] In 1865, for example, the first inn was opened in Yogyakarta and then the Mataram Hotel was opened in 1869.

[2] That's their regular publication. However, after tracing the traces of this newspaper, it turned out that its first publication was on January 15, 1877. Further research on the traces of the discovery of the first publication on January 15, 1877 with regular publications in 1903.

6. Pembrita Betawi - Batavia (Jakarta)

The Pembrita Betawi newspaper has many unique stories in it. This newspaper was right at the gate of the new era of journalism at that time and arguably done a great deal drove one of the leading "Inlandsche Journalisten" figures of that era, namely R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo.

R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo, who is renowned as the "Father of the National Press" and was awarded the title of National Hero, has been the editor-in-chief of Pembrita Betawi newspaper since April 1, 1902[1]. It was at Pembrita Betawi that Tirto's skills as an indigenous journalist began to be established, in Pramoedya's language, "Like a butterfly- the butterfly emerges from the pupa." Tirto's idea to establish the first women's newspaper Poetri Indies in 1908, also emerged when Tirto led Pembrita Betawi. The idea was written since he served as editor, namely in Pembrita Betawi edition No. 10, 14 January 1903 with the title "Kemadjoean Perempuan Boemipoetra" (Advancement of Indigenous Women).

It was Pembrita Betawi who previously gave birth to Ferdinand Wiggers[2]. Initially Wiggers was a controlling officer, then succeeded in becoming a journalist and editor in several newspapers, in addition to a well-known literary writer in low-key Malay. Apparently, all of Wiggers' success began when he worked as an editor at Pembrita Betawi on October 31, 1898. It was also at Pembrita Betawi that Lie Kim Hok, a prominent Chinese Malay literary writer, had played a role in his printing press.

This newspaper has been published regularly since December 24, 1884 in Batavia. The original editor was J. Kieffer, who with W. Muelenhoff was a co-manager. Pembrita Betawi was originally published by W. Bruining & Co, then the following year (1885) it was taken over by Muelenhoff. However, this newspaper changed hands many times, among others, to Karscboom & Co.; fell into the hands of Albrecht & Co. (1888), and then taken over by Albrecht & Rusche until the end of his life on December 30, 1916. This newspaper, originally written under the name Pembrita Betawi, was later changed to Pemberita Betawi. The subscription price is 2 gulden a month.

Towards the end of 1913, a new political consciousness grew among the indigenous people in Java. This situation spread confusion among non-native newspapers. Even though Pemberita Betawi was popular and somewhat pro-nationalist, he could not help but feel confused and difficult to compete with newspapers run by natives that mushroomed in 1912 and 1913. However, by 1913, the press in the Dutch East Indies was no longer a monopolistic industry. The birth of Indonesian national consciousness almost simultaneously produced an authentic indigenous press as the spokesperson for the nationalists. Betawi newsmen are at the threshold of a new era of journalism, complete with all the confusion it causes, but nevertheless they have contributed greatly to the birth of Tirto Adhi Soerjo as the Father of the National Press.

At that time, the Chinese press was still dependent on the Chinese readers of peranakan descent. This is different from Malay-language newspapers led by Indos (mix native and European descent) and Dutch-owned newspapers which speak Dutch. The press who want to keep their business, inevitably have to change their news coverage. This means that a more objective style of reporting is needed, even if it does not have to be openly sympathetic to the indigenous political movement. It was in that era that Betawi Newspapers began to include news about the Chinese and opened themselves to receive writings concerning the Indigenous people. In fact, in 1906, Pembrita Betawi published news on the translation of the Holy Qur'an in Japanese and Chinese as symbols of Islam.

[1] Pramoedya Ananta Toer in Sang Pemula (1985: 11) mentions that after leaving STOVIA Tirto immediately started his career at Pembrita Betawi starting as editor, then chief editor replacing F. Wiggers, and finally becoming in charge in 1902.

[2] Wigers played an important role in the press and literature in the Dutch East Indies. The importance of Wigers' role can be seen in the recognition of the magnitude of his role and contribution in giving the Indies color to the Malay language which soon developed into modern Indonesian.

7. Sinar Matahari - Makassar

The first edition of this newspaper was launched in June 1904 in Makassar, published by Brouwer & Co. Sinar Matahari rises every Monday and Thursday with a subscription rate of 6 gulden per year.

Not much is known about this newspaper, except that it is a competitor to the Makassar Newspaper. The readers of these two newspapers are mainly Chinese Peranakans. In 1907, the correspondents of the two newspapers wrote articles that berated each other. This was due to the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 which gave Asians a great deal of confidence who was often viewed as a second-class race. Judging from the readers' letters, the example of Japan has been used as an inspiration by the Chinese to unite and strive for progress. Japan's victory over Europeans was often discussed in Sinar Matahari—as was the Chinese press in Java and Sumatra at that time. This also reflects their latent dissatisfaction with the treatment of the Dutch colonial government throughout the Dutch East Indies. This at least explains the position of the Sinar Matahari newspaper regarding the formation of the "Chinese awakening" which began with the search for Chinese cultural identity for a nationalism, not only in the Dutch East Indies as a Dutch colony, but also in Southeast Asia which was under the British colony. This effort illustrates the need for the Chinese to have greater opportunities to lead life in the countries where they live. This nationalism was manifested in the formation of the Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (first Indonesian-Chinese nationalism movement) in Batavia which then spread rapidly, including to Makassar. In 1903, the Tiong Hoa Hok Tong association was founded, whose political stance was reflected in Sinar Matahari and Makassar News. At first they were only readers, but later many involved themselves as correspondents and editors. The newspaper closed in 1919.

8. Sinar Terang - Batavia (Jakarta)

Be careful! Don't confuse the Sinar Terang newspaper, which was published in Batavia, with Sinar Terang, which was published in Surakarta. Sinar Terang published in Surakarta, the first sample number was launched on October 31, 1885 by Vogel van der Hayden & Co in Surakarta. Meanwhile, Sinar Terang, which was published in 1886 in Batavia, was initiated by Yap Goan Ho, a printing businessman who specializes in printing books and printed materials for office and school purposes. Initially this newspaper was published regularly, only since June 25, 1888, Sinar Terang has been published regularly. Its first editor was an Indo (European descent) named W. Meulenhoff. Before becoming a journalist, Meulenhoff was a head of department at the Department of Public Works, then an editor at Pemberita Betawi. Except for one distributor in Serang, all of Sinar Terang's distributors are Chinese living in Bogor, Bandung, Cianjur, Sukabumi, Garut, Cirebon, Semarang, Demak, Surabaya, Tegal, and Padang.

Yap Goan Ho is apparently a businessman who wants to go all out in the mass media business. The scale of the printing company and the business that Yap had planned in the press and printing sector was enormous. According to Regeeringsalmanaak 1893, Yap invested up to 5000 gulden. Yep, for example, in 1894 attempted to publish a new newspaper called Chabar Berdagang. This sample edition of the newspaper devoted to commercial advertisers did not last long, as it failed to get an encouraging response from customers. In fact, two years before Chabar Berdagang was published, Yap had also tried to set up another printing company in Semarang, but there was no news of this printing activity after his birth. The financial crisis due to heavy investment is suspected to be the root cause of the bankruptcy and the closing of the Sinar Terang newspaper in 1898.

9. Tjaja Soematra - Padang, West Sumatra

By 1900, Tjahaja Soematra was one of five newspapers circulating outside Java. This newspaper was published by P Baumer & Co in Padang in 1897 and published twice a week. One of the journalistic attitudes of Tjahaja Soematra is reflected in the writings of his editor, namely Lim Soen Hin. There, Lim criticized the publication of the first edition of Alam Minangkabau newspaper, the first newspaper in Minangkabau and published in Padang. This newspaper is published every Saturday and is printed by the Naamlooze Vennootschap printery Snelpersdrukkerij “Insulinde” which has published Tapian Na Oeli, Insulinde, and Pertja Barat. Lim was furious because this newspaper prominently used high Malay or literary Malay and used Jawi (Malay-Arabic) letters, thus limiting its readers to only Minangkabau, Mandailing Muslims, and Angkola. The editorial is Middle Eastern oriented and his writings reflect orthodox Islamic tendencies, both from the perspective of the newspaper itself and its readers.

Reacting to the Alam Minangkabau newspaper, Lim wrote:

“Menilik kata-kata dan sedjarahnya, tiadalah akan berapa lama lagi, di kota Padang nanti ada fabriek kata Melajoe dan penjoeloeh mengobah edjaan dalam hoeroef Arab. Begitoelah temasja kemadjoen Alam Minang Kabau: Oelar berikoet sifat Binatang achir zaman!!!” begitu tulis Lim pada 1 April 1904.

("Looking at the words and their history, it won't be long before in the city of Padang there will be a Malay word factory and the instructor will change the spelling in Arabic. That's how the Minangkabau Nature progress tour: snakes and animal traits at the end of the age!!!” so wrote Lim on April 1, 1904.)

Lim is a peranakan Chinese from Padang Sidempuan who started his career in the last decade of the 19th century as editor of Tjahaja Soematra under Datoek Soetan Maharadja (1858–1921), a pioneer of the national press in Sumatra. Both Datoek Soetan Maharadja and Lim later became involved in a lengthy dispute with Dja Endar Muda, the editor of Alam Minangkabau. Through their comments and editorials, the three men accused each other and undermined the popularity of opposing newspapers. At this point, the problem is no longer Tjahaja Soematra's journalistic attitude, but how the competition among newspapers for market share is fiercer in Sumatra than in Java, because they are published and circulated in the same location. The desire to attract readers often gives rise to disagreements among editors.

Nevertheless, Tjahaja Soematra remains a newspaper that diligently appeals to indigenous leaders and indigenous people to care about progress and the need to pursue progress. Datoek Soetan Maharadja, for example, in Tjahaja Soematra complained about the lack of schools for indigenous children, in response to the writing of Retnodhoemilah of the 13 February 1909 edition.

Datoek Soetan Maharadja's writings became Tjahaja Soematra's journalistic attitude which reflected his newspaper's desire for Sumatrans to pursue modern progress while determined to preserve Minangkabau customs and traditions. The modernization model chosen is based on traditional Minangkabau customs, while using Western education for progress. The newspaper closed in 1933.

Seven Legendary Press Figures In 100 Old Newspaper Denny JA Collections

R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo (1880–1918) was a figure known as the “Father of the Indonesian Press.” Takashi Shiraishi in his book Zaman Bergerak (Age in Motion) mentions Tirto Adhi Soerjo as the first native native who moved the nation through his language through Medan Prijaji. He is the character Minke in the Buru Island Tetralogy by Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Thanks to Pramoedya's novel and his book Sang Pemula which raised the figure of Tirto Adhi Soerjo, this name became widely known and became a historical study. There is even an online media that uses the name Tirto, which is indeed inspired by Tirto Adhi Soerjo.

Tirto attended HBS Holland and STOVIA. However, because he was more busy writing in the mass media, he did not finish his medical school. Tirto's journalistic career began as editor of Pembrita Betawi newspaper and then Bintang Betawi with F. Wiggers. In Bandung, Tirto founded 3 newspapers, namely Soenda Berita (1903-1905), Medan Prijaji (1907) and Poetri Hindia (1908). Because it uses the Malay language and the entire production and publishing process is carried out by native natives, Medan Prijaji is finally considered the first national newspaper to be published. Medan Prijaji was very popular with the public at that time because there was a special rubric that provided free legal counseling.

In 1906, two years before the Budi Utomo association was born, Tirto had founded the first modern-style indigenous organization called Sarikat Priyayi. This association later gave birth to the Medan Prijaji newspaper (1907). Together with H.O.S Tjokroaminoto and Haji Samanhudi he founded the Sarekat Dagang Islam (SDI), which later became the Sarekat Islam (1909). Reports in the Medan Prijaji newspaper were often considered offensive to the Dutch government, so Tirto was often exiled to a remote place for months. Tirto Adhi Soerjo died on December 7, 1918. After reformation he was made a National Hero.

Ferdinand Wiggers (1862 – 1912), was a well-known journalist and writer in the Dutch East Indies. His journalistic career began by becoming the editor of Pembrita Betawi (1898). In addition he worked in several newspapers and other journals, including: Warna Sari, Bandera Wolanda, Pengadilan Hoekoem Indies (1898), which was changed to Taman Sari (1903). According to Kwee Tek Hoay—one of the 33 Most Influential Literary Figures in Indonesia, he is the son of E.F Wiggers. The editor and founder of the Malay-language newspapers Bintang Barat and Bintang Betawi is well-known as a writer whose works are in demand, including: Tjerita Njai Isah (published in up to five volumes), Boekoe Peringatan: Mentjeritain dari halnja seorang Prampoean Islam Tjeng Kao bernama Fatima, Raden Adjeng Aidali: soeatoe tjerita jang kedjadian di tanah Djawa (1910), Tjerita Dokter Legendre atau Mereboet harta (1902) and drama Lelakon Raden Beij Soerio Retno (1901). Ferdinand Wiggers was also the editor of the Bintang Betawi and Pembrita Betawi newspapers together with Tirto Adhi Soerjo, who later became known as the Father of the Indonesian Press. Ferdinand Wiggers had been Tirto's mentor in the field of journalism.

Abdoel Moeis (3 July 1886 – 17 June 1959) was an Indonesian poet, politician and journalist. He was a senior member of the Sarekat Islam and had been a member of the Volksraad (Dutch East Indies Parliament) representing the organization. Abdoel Moeis was inaugurated as the first National Hero by the President of the Republic of Indonesia, Soekarno, on August 30, 1959. He attended ELS school, then to STOVIA, but did not finish due to illness. After two and a half years working in the Departement Onderwijs en Eredienst (Department of Education and Religious Affairs), he left and became the editor of Bintang Hindia magazine, then Preanger Bode, and the magazine Neraca led by Haji Agus Salim. He pioneered the founding of the Technische Hooge School–Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB). This member of the Volksraad representing the Central Sarekat Islam is known as a writer with his work Salah Asuhan.

Lie Kim Hok, born in Bogor, West Java, (November 1, 1853–died in Batavia May 6, 1912 at the age of 58 years), was an Indonesian writer, a pioneer of Chinese Malay Literature “The Rintisan Period” (1875-1895), which is the period in which he wrote early Literary works in Low Malay (Bazaar Malay) language by both Dutch and Peranakan Chinese. Lie attended missionary schools and could speak Sundanese, Malay, and Dutch, although he could not understand Mandarin. His famous books are Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari and Grammar of Malajoe Batawi[1] (1884), and Tjhit Liap Seng, which is considered the first Chinese Malay novel. He obtained the printing rights for Pembrita Betawi, a newspaper based in Batavia.

Jan Fabricius, famous Dutch journalist and playwright. Entered the Dutch East Indies at the age of 20, became a journalist and then editor-in-chief of Preanger Bode. In addition, he was editor of a number of newspapers, such as Wereldkroniek, Spaarnebode and Nieuwe Courant. He is also known as a playwright, and has produced many works, including: Met de handschoen getrouwd (Marriage Through an Intermediary, 1906), Eenzaam (Alone, 1907) and De rechte lijn (The Right Way, 1910), which were performed hundreds of times by Rotterdam Theatre. His dramas that exploded were Dolle Hans (Boneka Hans. Drama Indo in three acts, 1916), which was box office in theaters in Rotterdam, and Totok en Indo (Totok and Indo, 1915), the highly successful drama of life in the Dutch East Indies. In 1949, the year the Netherlands recognized Indonesian Independence and Fabricius released a nostalgic piece about the colonial period entitled Tempo doeloe: Uit de Goeie Ouwe Tijd (Tempo Doeloe: From The Good Past, 1949).

G. Francis (1860–1915) was born into an English family. His grandfather, E. Francis, was a high-ranking official in the colonial administration of the Dutch East Indies. The name G. Francis immediately became famous after he published his work Tjerita Njai Dasima[2] (1896). In addition to writing literary works, G. Francis was active in the press, as editor of the weekly Pengadilan (1862-1898) in Bandung, as well as editor of Bintang Betawi in Batavia, replacing J. Kieffer who rose to leadership. When this newspaper closed in 1906, it moved to Pantjaran Warta (1909-1917). Tjerita Njai Dasima is published by Kho Tjeng Bie & Co, Betawi. In 1926 Druk F.G. Camoeni, Batavia reprinted this work by being filmed by the Tan Brothers and played by Indonesian and Indo-European actors (1929). Having had great success, Tan ventured to develop the story in Dasima II (1930). The new version of Nyai Dasima was filmed by Java Industrial Film (JIF) with Moh. Mochtar, Hadidjah, S. Soekanti, and Bissoe (1940). Furthermore, Chitra Dewi Film Production filmed Nyai Dasima with the title Samiun and Dasima. The players include Chitra Dewi, W.D. Mochtar, Sofia WD, Wahid Chan, and Fifi Young.

F.D.J. Pangemanann (1870–1910) was a journalist and novelist from Minahasa who was well known in the Dutch East Indies. Around 1894, Pangemanann became a journalist for the Malay-language daily, Bintang Betawi, in Batavia (now Jakarta). At that time he was already actively writing fiction. His first novel, Tjerita Si Tjonat (1900), was a huge success. The second and last novel, Tjerita Rossina, was published as a serial in a newspaper. Both are bandit stories and use a similar formula. In 1902. After Bintang Betawi closed (1906), Pangemanann worked for the newspaper Kabar Perniagaan (later renamed Perniagaan) owned by an Indonesian Chinese Peranakan businessman, Tjoe Toei-Jang. In 1906, he served as a founding member of the first press council of the Dutch East Indies. Pangemanann died in 1910.

[1] Grammar of Malay Betawi. Betawi or known in Indonesian as Bahasa Betawi is a dialect of Malay spoken in Batavia or known as Jakarta today. Betawi language or Betawi Malay dialect is spoken in Jakarta and surrounding areas include suburban areas of Jakarta.

[2] The Story of Njai Dasima this book tells the story of a njai who married an Englishman. Njai (spelled as Nyai) is Indonesian women who become Dutch concubine during Colonial Era. Many of Njai married with Dutch colonial bureaucrat or any whites European. Njai Dasima story is popular story in Indonesia.